HISTORY

When Trains Came to Shepherdstown

For a period of about 75 years, from 1879 until 1957, the trains stopped in Shepherdstown. Now they just pass through on their way to somewhere else. Maybe the engineer of a train has waved to you as you sat in Dr. Davis’ chair having your teeth cleaned, or maybe the sound of the train whistle has woken you up in the middle of the night. You have certainly had to wait in your car at the crossing while a train went by. That’s the way we think of trains here in Shepherdstown now, but back then, trains were exciting. Trains meant progress.

Not that trains were entirely new in 1879; trains had been around since 1830 when the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad laid a mile-and-a-half track near Baltimore. A round trip ticket cost 9 cents and people flocked to ride.1 By 1860, there were over 30,000 miles of railroad track laid in the United States. And by 1890, that number had grown to over 200,000. Until trains came along, horses (or mules) were the fastest way to get around. They pulled wagons or canal boats at about 4 or 5 miles per hour, depending on how loaded up the vehicles were. By the 1850s, trains could already go about four times that fast.2 Is it any wonder the people nicknamed the train the iron horse?

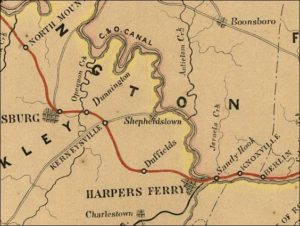

This 1858 map shows the various modes of transportation that were available to the people of Shepherdstown back then. A C&O Canal boat could be boarded right across the river. The B&O Railroad also could transport you east or west (if you could get a ride to Duffields or Kearneysville), but there was no north-south route at all. Travel remained restricted to foot or horses.

Bringing the Trains to Shepherdstown

People started talking about bringing the railroad to this area shortly after the Civil War. It’s hard for us to imagine now how important the trains were to the people of Shepherdstown back then. The railroads were seen as a way to help the region recover from the economic depression that followed the war. Shepherdstown had changed hands several times during the war and both sides had confiscated livestock and looted homes. The mills were ruined. Thousands of men had been killed during the war, and many more were left disabled. Women and their children had to fend for themselves.

However, it wasn’t easy to get the railroad going. Two different companies began planning to build a railroad in the Shenandoah Valley shortly after the Civil War: the Valley Railroad (VRR), with its supporters hailing from the southern Shenandoah Valley, and the Shenandoah Valley Railroad (SVRR), whose organizers were from Jefferson County in West Virginia, and Page and Warren Counties in Virginia.3 Both companies intended to build north-south lines through the Shenandoah Valley, which as you know is a fairly narrow strip of space. Both railroads were intended to connect at either end to already existing railroads (and not the same ones, either.)

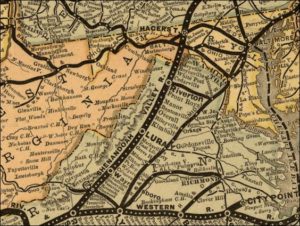

The SVRR wanted to build a railroad track from Hagerstown, Maryland, where it would connect with the Cumberland Valley Railroad (part of the Pennsylvania Railroad), to Salem, Virginia, where it would connect to the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. (The end point of the SVRR was ultimately changed to a small town called Big Lick (now Roanoke). The Valley Railroad was being built roughly parallel (and in some cases ran right next to) the SVRR track. The VRR connected to Salem and went south to Bristol, Virginia, on the Tennessee border. The VRR had the advantage of getting started earlier, because it passed through only one state, and connected to three railroads in between, so there was less track to lay. Three different state legislatures had to pass laws allowing for the SVRR railroad.4 This started in 1867 and took about 3 years to complete. Then the money had to be found to build it, and construction companies found to do the grading and lay the track. Work began in 1870.5

The people of Shepherdstown fought hard to have the train go through town, because it meant jobs for local people, and more commerce for the town. Shepherdstown had become the county seat during the Civil War (February 1865), because Federal soldiers who were stationed along the B&O Railroad could more easily protect it there. The town wanted very much to remain the county seat, and this may have been part of the struggle to bring a train to the town. One of the points put forward in favor of Charles Town as the county seat was its accessibility and that it had a railroad. In the end, the people of Shepherdstown won the right to have the train come through town, but lost the right to be the county seat the following year.6

Progress came at a cost. On March 30, 1870, Jefferson County voters approved bonds for $250,000 to pay for rights of way for the railroad, and the Shepherdstown town council put up bonds of $8,000 dollars.7 The bonds put up by Shepherdstown were contingent on railroad car shops and maintenance facilities being built in town, which would bring even more jobs to its people.8

Property through town had to be condemned, and some people had to find new places to live. Many townspeople felt they were not paid what their land was worth, and went to court to fight for a fair settlement.

The First Train

On the evening of January 1, 1879, the first train snorted into Shepherdstown. That’s right, snorted. At least, that’s the way the editor of the Shepherdstown Register reported it (see inset).

The very first train to Shepherdstown arrived on January 1, 1879. However, that was just a construction train. Although lots of people were on hand to see the first train arrive, the town decided to mark the event with a little more fanfare a week later. People from the SVRR, the contractors who built the track, and many other dignitaries were invited to attend, and were scheduled to arrive on the Fairfax from Charles Town at noon on that day, Wednesday, January 8. A parade made up of the Town Council, the local band and others started at Shepherd College (now McMurran Hall) and marched to the station to meet the train. It arrived at about 12:15 p.m. to loud cheering, music from Criswell’s Cornet Band, and the ringing of every church bell in Shepherdstown.9

Many prominent citizens made speeches, and among them, Colonel H. K. Douglas read an extract of an article he had written for the Shepherdstown Register in 1860, in which he talked about the necessity of a railroad for Shepherdstown. Colonel Douglas said that he “thanked God that he had lived to see this day; and that his greatest fear was that he should die and it would be inscribed on his tombstone ‘he was born in a town that never had a railroad;’ but now he could die in peace.”10

After the speeches were finished, the guests were escorted to the Entler Hotel, where a banquet was held in their honor, cooked by the ladies of the Reformed Church. Then at 5:00, the honored guests again boarded the Fairfax, the engineer blew the whistle and the train headed back to Charles Town.

Bridging the Potomac

It should be noted that when the first trains came to Shepherdstown, the railroad bridge across the Potomac was not yet finished, so trains could only come into Shepherdstown from the south and then head back again. The bridge was started on March 17, 1880, and a crew of 35 men finished it in just under four months, on July 7 of that year. Two days later, the first train crossed the Potomac.11

Finishing the Line

By December 1879, trains ran from Shepherdstown south to the Shenandoah River, via Charles Town, Berryville, Ashby and Riverton. By May of 1881, excursion trains were running to Luray Caverns, and the railroad track went all the way to Waynesboro.

In early August 1880, only five miles of track were still unfinished on the road between Shepherdstown and Hagerstown. The track was finished on August 1312, and on August 25, The Herald and Torch Light (Hagerstown) was reporting train schedules between the two towns. The train left Shepherdstown at 7:17 a.m. and was scheduled to arrive in Sharpsburg 8 minutes later and then traveled on to Hagerstown. The trip to Hagerstown took just over an hour. The train left Hagerstown each evening at 5:30 and returned to Shepherdstown at 6:35. By April of 1882, you could travel from Hagerstown to Shepherdstown in just 46 minutes.13

Trains Changed People’s Lives

The trains changed the way people lived their lives. Excursion trains allowed people to make trips that hadn’t been practical before. There were excursion trains to the local fairs, to Luray Caverns, and even to Shepherdstown to commemorate those who lost their lives in the Civil War. In 1911, when Jefferson County went “dry” and the sale of liquor was prohibited, many people of the county made “unscheduled” excursions to Maryland and Winchester, where a person could still buy a drink legally.

In 1880, when Shepherdstown became connected by railroad with New York City and Philadelphia, mail from those cities suddenly began to arrive the same day it was sent, and newspapers showed up the same day they were printed.15

Faster communication was now available all up and down the line, for while the track was being laid for the trains, Western Union was also stringing wire for a telegraph line. Until telephones were installed in Shepherdstown, in Dec. 1898, there was no faster way to send a message.

No one appreciated this fact more than a man named George Carter. On October 31, 1884, Mr. Carter robbed the men on a ballast train (a repair crew train) in Virginia, and a telegram was sent from Shepherdstown to Hagerstown to warn police there that Mr. Carter was on the train. When he got off at Hagerstown, the police were on hand to meet Mr. Carter, and to arrest him. Imagine a thief robbing train employees and then using the train to make his escape! But it was the fastest getaway around.16

Goods and passengers now arrived from all over, faster than ever before. Even the Liberty Bell was a passenger on January 6, 1902, on her way to an exposition in Charleston, South Carolina; it was estimated that a thousand people crowded the depot to see her.

Once the trains came, there were fires started by the trains, cinders polluted the air, it was a very dirty business. In early August of 1885, a freight car loaded with dry bark caught fire, probably from sparks from the engine of the train it was connected to. The trainmen tried to put out the flames but were unsuccessful.17

Livestock were sometimes run over by the trains. There were accidents involving people, too. The day that the first train arrived in Shepherdstown, a little girl named Louise Shepherd was nearly run over.18 In October 1906, a man named Gibson Ball was hit by a freight train one night as he was walking on the tracks.19

A terrible accident occurred at the station on November 30, 1909, just a few days after it was finished. A prominent farmer from Berkeley County, Willis Hodges, was crossing the track with his horse and buggy. At the same time, the freight train, which had been at the grain elevators across from the station, backed up and ran over the buggy. Mr. Hodges was crushed to death; he was just 31 years old. The accident was even more tragic because Mr. Hodges’ wife had died less than two weeks earlier, and their four little girls were left orphans. An inquest held a few days later found that there was no negligence on either party’s part.20

On December 30, 1909, Miss Sallie Hill of Shepherdstown, a 54-year-old woman employed as a cook for two sisters in Shepherdstown, filed suit against the Norfolk & Western Railroad for the amount of $3,000. This was quite a large sum of money in those days, roughly $60,000 in today’s terms. A couple of months before, on Oct. 13, Miss Hill had been traveling from Harrisburg to Shepherdstown, first on the Cumberland Valley Railroad, then on the SVRR. When she got to Hagerstown, she was told to get on the train standing in front of the station. However, when the conductor came around asking for tickets, he wouldn’t accept hers, because it was a regular ticket and the train she was on was the excursion train for the Hagerstown fair. The conductor put Miss Hill off the train a couple of miles out of town, and she had to walk back to the station and take another train. We have not found out whether Miss Hill got her money, but will let you know as soon as we do.

The Weather

Mighty though they were, the trains were not immune to bad weather. Several times during their history in Shepherdstown, bad weather briefly stopped the trains from coming through.

During the second week of Feb. 1895, there was a big snowstorm, coupled with very low temperatures, down around 10 below at night, and accompanied by gale force winds. The newspapers were full of reports of boys with frostbitten ears and of one girl who went over an embankment with her sledding party and broke her arm. The trains (now owned by the Norfolk & Western company) got stuck in Charles Town and Berryville, or in big drifts somewhere. Passengers got stranded, and men went out in sleighs to bring in the mail that was stuck because the trains couldn’t get through.

Then, as now, bad weather was big news. Nowadays, we have radio, TV and the internet to tell us what’s going on and help us feel connected to the outside world. Back then, when there was inclement weather, people were essentially cut off, especially when the telegraph lines were down. One of the dangers was in the spread of misinformation, which was the case during the devastating flood at Johnstown in June 1889.

The rivers of the entire region of Pennsylvania, Maryland and West Virginia, including Shepherdstown, overflowed their banks. The Bucks County Gazette in Pennsylvania reported, apparently erroneously, that the railroad bridge in Shepherdstown was completely destroyed.21 Many bridges were destroyed, but we have not found mention of this particular bridge succumbing to the water. It does appear that the roadway bridge was destroyed. This bridge was made of wood, and was closer to the water than the railroad bridge. The Shenandoah Valley Railroad company had decided back in 1887 to replace the old wooden bridge with an iron one, and this appears to have been done, although the wood trestling on the Maryland side may have still been wood. On April 3, 1890, the Herald and Torch Light reported that a bill had been passed in the Maryland State Legislature to “compel the Maryland and Virginia Bridge Company to repair its bridge at Shepherdstown or forfeit its charter”. We believe this was the roadway bridge, as the train schedules from Hagerstown south continued to be published in the newspaper.

The Station

When the trains first came to town, there was initially no station, or depot, as it was then called. The original Shepherdstown station was not built until sometime between 1880 and 1884.14 We know that there was a depot by November 24, 1884, because there is a report in the Shepherdstown Register of its safe being blown open by professional thieves, and $60 dollars stolen (see inset).

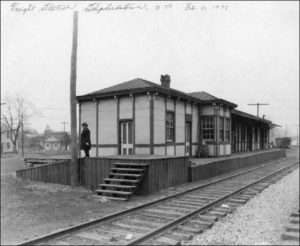

In the early days, both freight and passengers traveled on the same trains, and there was a single station for both. The first train station was a wooden structure, located south of Princess St. (behind the Southern States).22 It looked very much like the Antietam station at Sharpsburg. Later the current station was built exclusively for passengers, and the old station was used exclusively for freight.

The New Passenger Station

On November 20, 1909, the new passenger station was completed. It was opened to passengers on Dec. 1 of that year. The total cost was about $22,000.23 It is clear from reports in the Shepherdstown Register (view full text of article) that the community was very proud of the station. It was from the Norfolk & Western’s top-of-the-line blueprint, aside from the large union stations.

A particularly popular feature of the new depot was a railway shed that ran 250 feet along the tracks, so that people could wait for the train outside in both hot and wet weather and still be comfortable. The station had two waiting rooms, “one for white persons and one for colored persons.”24 Each waiting room had front and rear entrances, and each had a pair of restrooms. The editor of the Register writes proudly of the modern conveniences – restrooms, running water, a heating system, drainage system and electric lights.

The station agent’s office was in the center of the building, next to where the current kitchen is now. The bay windows looking out over the tracks had iron gratings to protect the windows.

The old wooden station became the freight-only station. At the same time, the track was re-aligned and straightened, and a new and higher bridge was built over the Potomac. This was to accommodate the heavier trains that were being used.

The End of Trains

On June 27, 1957, the Station at Shepherdstown was closed by court order, in light of Norfolk & Western losses. Fewer people rode the trains in the prosperity of post-World War II America, because more and more people were able to afford their own cars. The station had been becoming less and less important in town, whereas the gas station that used to be where the Blue Moon is now was probably gaining in importance. People could get their information from radio and TV. The telegraph wasn’t needed as much, because nearly everyone had a telephone.

The Station Today

For a few years, the station remained empty. In the mid-1960s, the railroad used the station for storage. Then in 1990, a movement to save and restore the station was started under the guidance of the Corporation of Shepherdstown and Mayor Audrey Egle. A working committee was formed under the Historic Shepherdstown Commission, consisting of local citizens Robert Fodor, Harvey Heyser, and Joseph Snyder. The committee prepared plans for the preservation of the station, and in 1992 Senator Robert C. Byrd added $500,000 to an appropriations bill to aid in the restoration of the station as a center for community and health services. Renovation design was provided by the architectural firm of Rust, Orling, and Neale. Antietam Construction was general contractor for the major project.

September 23, 1996 marked the official sale of the station by the Norfolk & Western Railroad Company to the Corporation of Shepherdstown. The deal was made in Senator Byrd’s office in Washington, DC. Then Mayor Vincent Parmesano represented the town. The Railroad agreed to sell Shepherdstown the station for a dollar. Sen. Byrd provided a dollar in coins to seal the exchange.

The community center in the former main waiting room of the station opened for limited public use in July 1997 while construction continued. Dr. Paul Davis opened his dental office in the former freight and baggage room at the north end of the station in May of 2001.

On October 27, 2001, the newly renovated station was dedicated in a ceremony and Senator Byrd was the main speaker. The station was packed with people, and the crowd overflowed into the parking lot.

Renovation continued and a fully-licensed commercial kitchen was equipped in 2002. Today, the station continues to be managed on behalf of the Corporation of Shepherdstown by The Station at Shepherdstown, Inc., which was formed as a non-profit corporation in 1992.

The Station is again an active part of a vibrant, thriving community. Dr. Davis cares for our dental health in his offices, and in the community center, there are lots of options to nourish the body and mind. During the week, you can take a class in yoga, belly dancing, Morris dancing, karate, and the like; on Saturdays, there are private events such as weddings and birthday parties; and on Sundays, there are church services and chamber music.

Epilogue

Things have a way of coming full circle, and although we of the board believed that the preservation of the station was finished (although maintenance will never be), we recently learned that it was not. On Wednesday, Dec. 8, 2004, Howard Mills, Treasurer of Station at Shepherdstown and also a member of the Shepherdstown Town Council, received a phone call from a man who said he had something that belonged to the station. The man said that he was calling on behalf of another man who, while a student at Shepherd College, had taken the Shepherdstown station sign as a prank. Now all these years later, this man’s conscience was weighing on him, and he wanted to give back the sign, but only on condition of anonymity. Howard met up with the caller, who handed over not one but three signs: the one that had been on the station shed (seen here in a 1933 photo), and two signs that marked the Maryland/West Virginia state line. We believe that the Shepherdstown sign may be the original that first hung in 1909 when the station was built, and now, nearly 100 years later, it has found its way back home.

Endnotes

[1] Incidentally, we have the B&O Railroad to thank for the name “train.” In 1830, the B&O used the term “train of cars” in its advertising, and the name stuck. (Everyday Life in the 1800s, p. 71)

[2] Everyday life in the 1800s, p. 71.

[3] Hildebrand, John R., Iron Horses in the Valley, Shippensburg, Pa.:Burd Street Press, 2001, p. 6.

[4] Ibid, p. 19.

[5] A History of Rockingham County, John W. Wayland, Ph.D., chapter 12. Published 1912 and online at http://www.rootsweb.com/~varockin/wayland/book_toc.htm.

[6] Bushong, Millard Kessler, A History of Jefferson County, West Virginia, Charles Town, W. Va.: Jefferson Pub. Co., 1941, pp. 197, 202, 209-10.

[7] Hildebrand, John R., Iron Horses in the Valley, Shippensburg, Pa.:Burd Street Press, 2001, p. 21.

[8] So it’s interesting to note that in the June 29, 1881 edition of Hagerstown’s Herald and Torch Light, there was a news article about Charles Town and Shepherdstown competing for the right to have railroad car shops built in their respective towns. Perhaps Jefferson County also had some expectations for the money its citizens put up. Later, Herald and Torch Light editors jumped into the competition, maintaining that Hagerstown would also be a good pick, despite its geographical disadvantage of being at the end of the line. Millard Bushong says in his book that shops were built in Shepherdstown, but were torn down a few years later. A History of Jefferson County by Bushong, p. 233.

[9] Shepherdstown Register, Sat., Jan. 11, 1879, p. 2. Vol. 14, No. 23.

[10] Ibid.

[11] The Herald and Torch Light, July 14, 1880, p3. Vol. 66, No. 49.

[12] The Herald and Torch Light, Wed. Aug. 18, 1880, p. 3

[13] Shepherdstown Register, Saturday, Apr. 29, 1882, p. 4. Vol. 17, No. 36.

[14] See Shepherd’s Town III, p. 56.

[15] There are mild complaints in the Shepherdstown Register on Dec. 5, 1884, when the company changed its schedule and mail and newspapers from New York and Philadelphia arrived the day after they were sent. However, the schedules were later switched back and everyone was happy again.

[16] The Herald and Torch Light, Wed. Sept. 04, 1884, p.3

[17] The Herald and Torch Light, Wed. Aug. 13, 1885, p.3

[18] Shepherdstown Register, Sat. Jan. 11, 1879, p. 2. Vol. 14, No. 23

[19] Evening Times (Cumberland, MD) Tuesday, Oct. 2, 1906, p. 1

[20] Shepherdstown Register, Thurs. Dec. 2, 1909, p. 3. Vol. 44, No. 50

[21] Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA. Thurs. June 6, 1889, p. 1

[22] See Shepherd’s Town III, p. 56.

[23] Based on CPI factor tables, that would be about 360,000.00 in today’s terms. ($20,000/.056)

[24] Shepherdstown Register, Oct. 18, 1909, p. 3, Vol. 44, No. 48.